Challenges and Opportunities for AI and Kilometer-Scale Climate Modelling of Precipitation

Challenges and Opportunities for AI and Kilometer-Scale Climate Modelling of Precipitation

Author: Emanuele Silvio Gentile, Dr

The preprint on which this post is based is available here.

One of the enduring challenges in weather and climate modelling is not predicting how much it rains, but when. The diurnal cycle of precipitation, the systematic daily rhythm through which rainfall builds, peaks, and decays, emerges from a tight coupling between radiation, surface fluxes, boundary-layer growth, convection, cloud microphysics, and mesoscale organisation. Because it integrates processes across scales, the diurnal cycle has long served as a stringent test of physical realism in atmospheric models.

Historically, even state-of-the-art weather and global climate models have struggled with this diagnostic. Rainfall over land tends to begin too early in the day, peak prematurely in the afternoon, and decay too rapidly overnight. Nocturnal precipitation, a defining feature of many continental and monsoon regions, is often weak or entirely absent. Yet these same models can perform well on bulk metrics such as monthly means or spatial correlations, creating a misleading impression of skill.

In a recent preprint, we revisit the diurnal precipitation cycle as a process-level benchmark, using it to compare a state-of-the-art AI weather prediction system (GraphCast), a widely used reanalysis product (ERA5), satellite observations (IMERG), and a global convection-permitting simulation at 5-km resolution. The central question is simple: what does the diurnal cycle reveal that headline skill scores do not?

Models and datasets

The comparison spans four distinct modelling paradigms. IMERG provides the observational reference, offering high-temporal-resolution satellite estimates of precipitation. ERA5 represents the best current synthesis of observations and model physics and serves as the training backbone for many machine-learning systems. GraphCast, a graph neural network trained on ERA5, exemplifies the new generation of data-driven weather models capable of producing skilful forecasts at unprecedented speed. Finally, a global 5-km Unified Model simulation offers a view of what changes when deep convection is largely explicitly resolved rather than parameterised.

All datasets are analysed consistently, focusing on boreal summer (JJAS) and decomposing precipitation into its mean state, the amplitude of the diurnal harmonic, and the phase (local solar time of peak rainfall).

Diagnosing the diurnal cycle

To move beyond mean fields, we decompose precipitation into its leading diurnal harmonic. Two quantities are particularly informative: the amplitude, which measures how strongly rainfall is modulated by the daily cycle, and the phase, which indicates the local time at which precipitation peaks.

These diagnostics allow us to distinguish between models that merely reproduce the right amount of rain and those that capture the physical processes governing its evolution through the day.

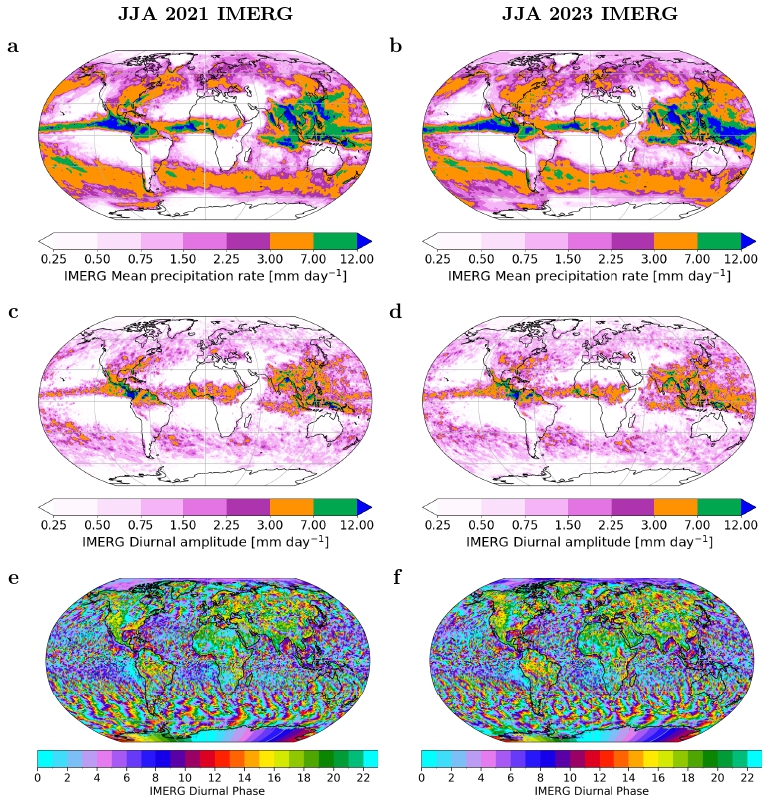

A stable observational reference

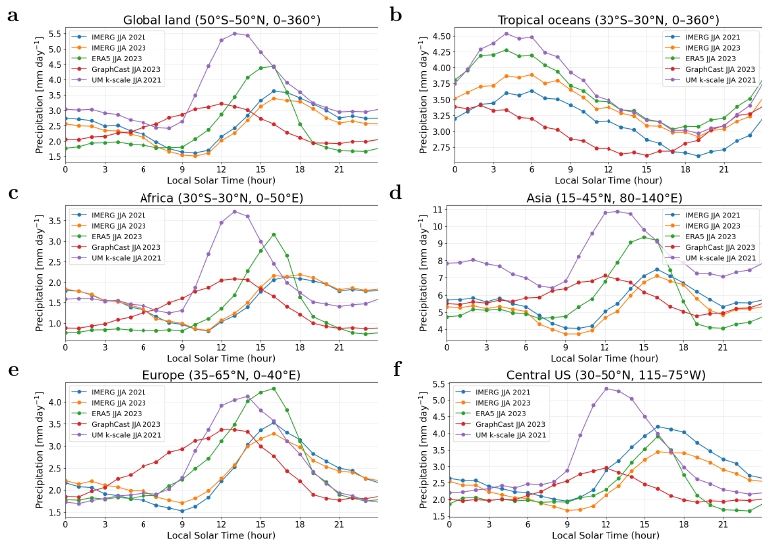

Before comparing models, it is essential to establish whether interannual variability could confound the analysis. Using IMERG observations for boreal summer 2021 and 2023, we find that the global diurnal precipitation cycle is remarkably stable.

Mean precipitation patterns differ only modestly between the two seasons, with 2023 slightly wetter over parts of the tropical oceans. More importantly, the structure of the diurnal cycle itself — amplitude and timing — is nearly unchanged. Strong diurnal amplitudes persist over continental interiors and coastal regions, while precipitation peaks consistently occur in the late afternoon to early evening over land and during the early morning over tropical oceans.

This stability confirms that the seasonal mismatch between datasets (IMERG and the UM 5-km simulation in 2021 versus ERA5 and GraphCast in 2023) does not compromise the intercomparison. The diurnal cycle provides a robust, physically interpretable benchmark against which different modelling approaches can be evaluated.

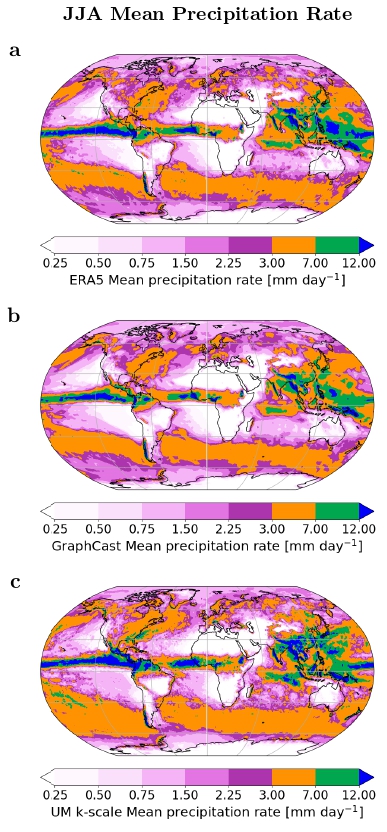

Mean precipitation: agreement without physical insight

At first glance, all three models — ERA5, GraphCast, and the 5-km Unified Model — reproduce the broad spatial structure of observed mean precipitation. Tropical rainfall maxima along the ITCZ and over the Maritime Continent are evident, as are secondary maxima over regions such as the Great Plains, central Africa, and the Southern Ocean.

However, this apparent agreement is deceptive. Mean precipitation integrates over the full diurnal cycle and therefore masks compensating errors.

ERA5 overestimates rainfall along the eastern Pacific ITCZ and underestimates it across large parts of the Maritime Continent. GraphCast broadly mirrors the ERA5 pattern but produces noticeably smaller regions of intense rainfall, with underestimations of up to ~5 mm day⁻¹ across parts of the Atlantic and Pacific ITCZ.

The experimental 5-km Unified Model reproduces the location and magnitude of tropical precipitation maxima more faithfully, but at the cost of a substantial wet bias in the midlatitudes, particularly over the Southern Ocean and parts of Europe and North America.

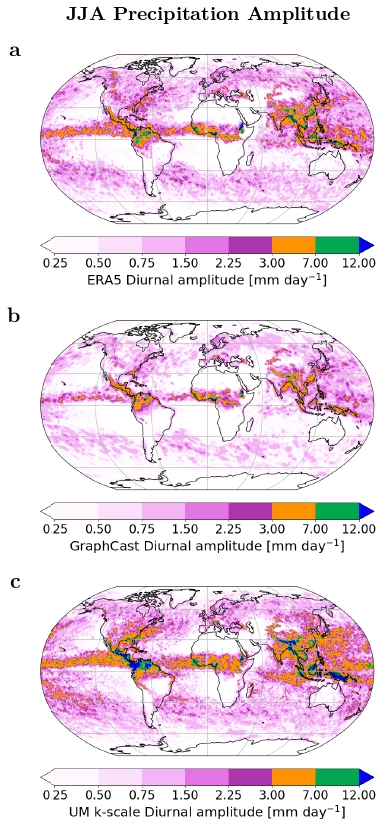

Diurnal amplitude: where models begin to diverge

Much larger discrepancies emerge when considering the amplitude of the diurnal precipitation cycle.

ERA5 substantially underestimates this amplitude. Over the Great Plains, diurnal modulation is weak and spatially fragmented, while over the Maritime Continent and coastal Mexico the areas of strong diurnal variability are far smaller than observed.

GraphCast not only inherits these deficiencies but often amplifies them, producing systematically weaker amplitudes across primary and secondary convective regions.

By contrast, the 5-km Unified Model closely matches observed diurnal amplitudes across most regions, with only minor regional biases.

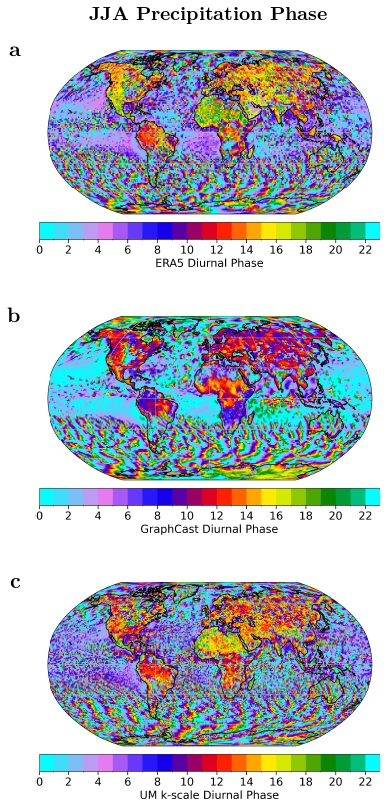

Phase: timing errors dominate over land

The timing of peak precipitation provides the clearest separation between modelling approaches.

ERA5 exhibits a pronounced bias toward premature rainfall over land, with precipitation peaking around midday or early afternoon rather than late afternoon or evening.

GraphCast further degrades this behaviour, concentrating rainfall unrealistically near local noon and producing very weak nocturnal precipitation. Over oceans, GraphCast also peaks too early, failing to reproduce the observed early-morning maximum.

The 5-km Unified Model shows clear improvements in nocturnal precipitation and captures several regional phase characteristics, although early afternoon peaks persist over some land regions.

Land–ocean contrasts: organisation matters

Domain-averaged diurnal cycles over land and ocean further clarify these behaviours.

ERA5 broadly reproduces the tropical-ocean diurnal cycle but peaks too early over land and underestimates nighttime rainfall. The 5-km Unified Model substantially reduces these nocturnal deficits, while GraphCast exhibits the largest phase bias, peaking roughly four hours too early and failing to capture organised nocturnal convection.

Discussion and conclusions

This analysis provides a process-based perspective on the strengths and limitations of AI-based weather prediction when evaluated against a physically demanding benchmark: the diurnal cycle of precipitation.

GraphCast successfully reproduces the large-scale spatial distribution of mean rainfall, reflecting the information content of its ERA5 training data. However, it systematically underestimates diurnal amplitude and substantially degrades the timing of precipitation, particularly over land. In several respects, GraphCast amplifies known ERA5 biases, producing a compressed diurnal cycle dominated by premature, surface-forced convection and weak nocturnal rainfall.

In contrast, the experimental global 5-km Unified Model demonstrates clear benefits of explicitly resolving deep convection and mesoscale organisation. Improvements in diurnal amplitude and nocturnal precipitation bring the simulation closer to observations, particularly over regions dominated by organised convection. Nonetheless, persistent wet biases and early afternoon peaks highlight that even kilometre-scale models remain sensitive to boundary-layer physics, microphysics, and scale-aware convective closures.

Overall, neither AI-based nor physics-based approaches fully resolve long-standing deficiencies in the diurnal precipitation cycle. The diurnal cycle therefore remains a crucial and physically interpretable benchmark for evaluating future weather and climate models. Progress will likely require hybrid AI–physics frameworks that combine the physical realism of kilometre-scale simulations with the computational efficiency of AI, and that explicitly target sub-daily variability during model development and training.

What this implies for AI weather prediction

GraphCast represents a major advance in weather forecasting. Its computational efficiency and forecast skill make it operationally transformative. However, the diurnal cycle exposes a fundamental limitation of purely data-driven approaches trained on reanalysis products: they cannot outperform the physical realism of their training data at the process level.

This is not a failure of AI, but a reflection of how learning systems work. AI models excel at reproducing patterns that are present in the data. They do not, on their own, recover physical processes that are systematically missing.

Why kilometer-scale physics still matters

The global 5-km simulation demonstrates that explicitly resolving deep convection alters not just the magnitude of precipitation, but its temporal character. Nocturnal systems emerge more naturally, amplitudes increase, and phase errors are reduced. While kilometer-scale modelling does not eliminate all biases, it provides a physically grounded reference against which both parameterised models and AI systems can be evaluated.

Toward hybrid futures

The broader implication is not a choice between physics and AI, but their integration. Convection-permitting simulations offer a pathway to improve both parameterisations and machine-learning models, whether through training data, physically informed loss functions, or hybrid architectures that embed constraints directly into learning systems.

The diurnal precipitation cycle should play a central role in this effort. As a diagnostic, it reveals whether models merely look right in aggregate or behave realistically in time.

Final reflections

Sub-daily precipitation is not a niche detail. It is a window into how models represent the atmosphere. By focusing on when rain falls, rather than only how much, we gain sharper insight into the strengths and limitations of both AI-based and physics-based weather prediction systems.

📌 Preprint available here:

The preprint is available here.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: