Kilometer-Scale Climate Intelligence for a Regenerative Urban Future

Kilometer-Scale Climate Intelligence for a Regenerative Urban Future

Author: Emanuele Silvio Gentile, Dr

One of the paradoxes of climate-informed design is that while global climate models have become increasingly robust, their coarse scale often limits their usefulness for local decision-making [1-2]. The models that underpin international assessments typically resolve the atmosphere at 50 to 200 kilometres, yet the interventions that determine ecological and social resilience, restoring a wetland, safeguarding a biodiversity corridor, designing an urban cooling strategy, unfold at scales of tens or hundreds of metres [3]. Bridging this disconnect between abstract global projections and the lived experience of climate on the ground is one of the central challenges of bioplanning.

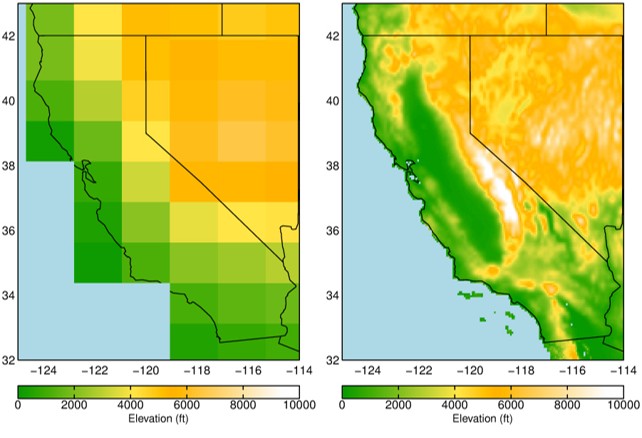

Recent breakthroughs are beginning to close this gap. A new generation of high-resolution datasets now makes it possible to model temperature, precipitation, solar radiation and humidity at resolutions finer than one kilometre. CHELSA-BIOCLIM+ [4], for instance, provides global, downscaled climate surfaces tailored for ecological applications, while new land-cover projections aligned with IPCC scenarios [5] allow planners to anticipate how landscapes may evolve under different socioeconomic pathways. Figure 1 illustrates this leap in detail: where older maps smoothed climate over entire regions, kilometre-scale data reveals the fine structure of valleys, ridges, and coastlines that shape ecological function.

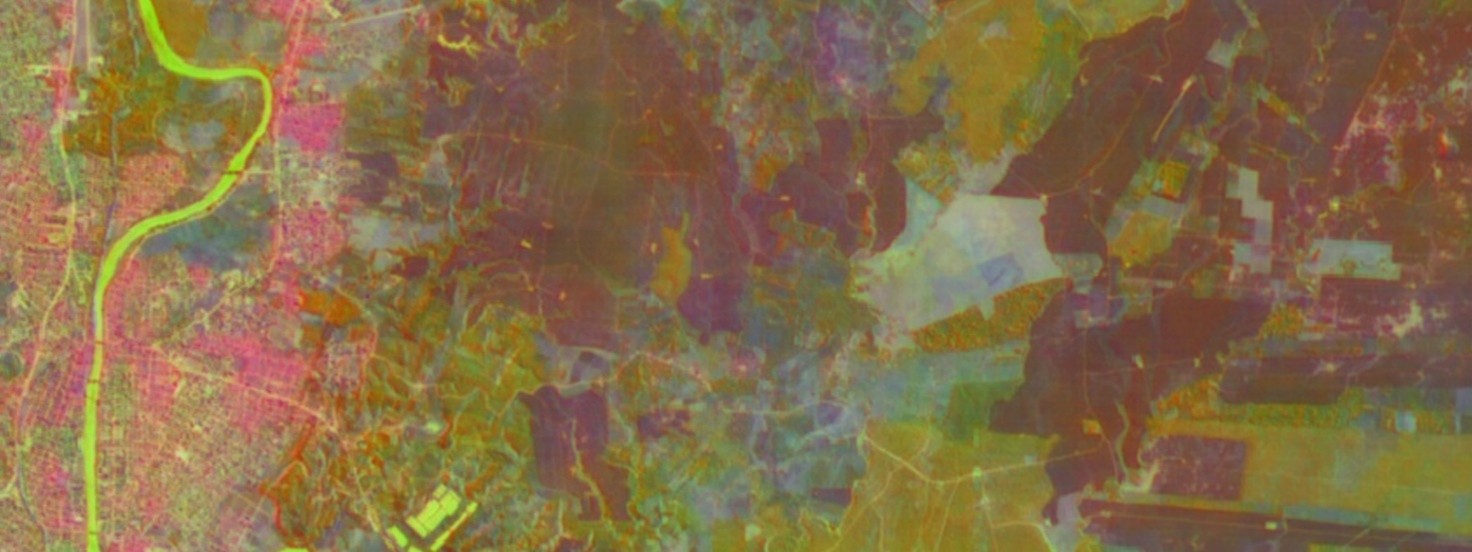

For the first time, planners can identify micro-refugia, assess species’ habitat suitability, or design conservation corridors with a resolution that matches ecological realities. Equally transformative is the arrival of artificial intelligence in climate science. NASA and IBM recently introduced the first open-source foundation model for weather and climate, which allows kilometre-scale downscaling, extreme-event forecasting, and flexible seasonal scenario analysis. By fine-tuning the model with local data, planners and communities gain access to forecasting capacity that until recently required scarcely available supercomputing resources. At the same time, Google DeepMind’s AlphaEarth Foundations integrate satellite observations with generative AI to anticipate floods, wildfires, and heatwaves across scales [7]. Operational tools like Flood Hub, FireSat and the Solar API (the latter for solar and energy systems installations) are already assisting countless countries in monitoring disaster risk and optimising urban infrastructure. Figure 2 highlights the high-realism of the output of this workflow: raw climate and Earth-observation data feed through foundation models and AI algorithms to produce microclimate maps, disaster risk forecasts, and design-ready intelligence.

These innovations are not simply technical feats. They mark the emergence of a new planning paradigm. With kilometre-scale data and AI-enabled analysis, it becomes possible to simulate how an urban expansion might alter local rainfall patterns through to 2100, or how a wetland restoration will affect water availability under a plausible 2°C warmer world. Hydrological changes, soil moisture dynamics, species distributions, even the spatial variability of urban heat, all can now be assessed with a fidelity that aligns with the scales at which communities and ecosystems operate. For bioplanning, this is the difference between designing against an abstract backdrop and designing in tune with the actual climatic grain of place.

The implications are profound. Conservationists can safeguard climate refugia and connectivity corridors, municipalities can test the resilience of green infrastructure under future extremes; architects and engineers can integrate climate intelligence into the earliest stages of design. And crucially, these assessments are transparent and reproducible. Projects such as Supernature Lab’s regenerative frameworks can now be monitored and evaluated with science-based intelligence that fosters trust across biodiversity, carbon, and infrastructure sectors.

The convergence of high-resolution climate data, backed by increasingly high-fidelity physical understanding and representation, along with the rapidly emerging AI innovations in climate modelling is therefore more than a technical advance. It represents a paradigm shift for sustainable urbanism: one in which design and policy can finally align with the climatic realities of place, informed by the precision and speed of next-generation data. The ecological cities of tomorrow will not be imagined in spite of the climate system, but in dialogue with it.

References

- Schneider, T., Leung, L. R., and Wills, R. C. J.: Opinion: Optimizing climate models with process knowledge, resolution, and artificial intelligence, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 7041–7062, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-7041-2024, 2024.

- Slingo, J., Bates, P., Bauer, P. et al. Ambitious partnership needed for reliable climate prediction. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 499–503 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01384-8

- Smith, A. P., Yung, L., Snitker, A. J., Bocinsky, R. K., Metcalf, E. C., & Jencso, K. (2021). Scalar mismatches and underlying factors for underutilization of climate information: Perspectives from farmers and ranchers. Frontiers in Climate, 3, Article 663071. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2021.663071

- Karger, D.N., Conrad, O., Böhner, J., Kawohl, T., Kreft, H., Soria-Auza, R.W., Zimmermann, N.E., Linder, P., Kessler, M. (2017). Climatologies at high resolution for the Earth land surface areas. Scientific Data, 4, 170122. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.122

- Hengl, T., de Jesus, J. M., Heuvelink, G. B. M., Gonzalez, M. R., Kilibarda, M., Blagotić, A., Shangguan, W., Wright, M. N., Geng, X., Bauer-Marschallinger, B., Guevara, M. A., Vargas, R., MacMillan, R. A., Batjes, N. H., Leenaars, J. G. B., Ribeiro, E., Wheeler, I., Mantel, S., & Kempen, B. (2021). SoilGrids250m: Global gridded soil information based on machine learning. Earth System Science Data, 13(2), 415–434. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-415-2021

- https://today.ucsd.edu/story/new_high_resolution_climate_projections_aim_to_better_represent_extreme_eve?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- https://deepmind.google/discover/blog/alphaearth-foundations-helps-map-our-planet-in-unprecedented-detail/

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: